The Indictment’s Illusion of Proof

A courtroom document can appear to speak with the authority of history. When a trial ends and the press reports on its outcome, the indictment is often quoted as though it were a factual account of what transpired. To the casual reader, its contents can seem indistinguishable from what the jury actually heard and weighed.

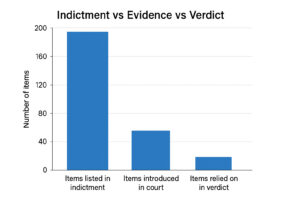

Yet this is misleading. An indictment is not a chronicle of events. It is a declaration of intention: what the Crown means to prove. The inclusion of photographs, police logs, medical records, or emails does not mean these ever reached the jury. Many remain unopened, untested, unexplained.

The law draws a firm line. Something becomes evidence only once it is introduced, authenticated, and admitted in court. Until that moment, a production is nothing more than a placeholder on a list. But when newspapers treat the indictment as though it were synonymous with the trial, the public is left with the sense of a case supported by overwhelming corroboration. The mere number of listed productions comes to feel like proof, even when most were never used.

This illusion has consequences. It erodes the presumption of innocence, allowing appearances to replace the rigour of proof. It also shapes perceptions long after conviction. A claim of wrongful verdict seems irrational when the indictment, faithfully reproduced in the press, appears to contain mountains of evidence. Few pause to notice that the actual conviction may rest on only a small fraction of that material.

A natural reply is that none of this matters: the jury convicted, and that is what counts. But here lies the crux of the problem. The jury decides on what is presented. The public judges on what is listed. These are not the same thing. One is a tested body of evidence, however imperfect. The other is a projection of what might have been tested, yet often was not.

What makes this more than a legal subtlety is its epistemic dimension. Human beings are poor at separating the familiar from the true. Psychological studies have shown how repetition alone can transform suspicion into certainty. When indictments are echoed in headlines and reports, their contents take on the aura of established fact. The list of productions begins to look like proof simply because it has been repeated as proof.

This leaves us with a troubling question. If an indictment can give the impression of abundant evidence, while the actual trial rests on only a fragment of that material, and the press then amplifies the illusion by reporting the indictment as though it were the verdict, are we making judgements about guilt on the basis of truth, or merely on the appearance of it?